An unearthed resource

By Byard Duncan, Senior Writer, The Ithacan | April 23rd, 2009

The road leading to Ron Carter’s trailer is made of red clay that melts away a little every time it rains. Truck traffic has created an obstacle course of tall divots that punch at the bottom of cars, rattling spines and scraping mufflers. Some lawns along the way host bathtubs full of garbage or rusty drums belching out dark smoke. Others have drill pads and cranes that stab 200 feet into the air. This is Dimock Township, the speck on Pennsylvania’s map that just became ground zero for America’s energy future.

Carter, like his trailer, is white and jagged with little hints of warmth tucked into the corners. Words slip out of his mouth in terse grunts, moving under his mustache and past the copper cross dangling from his neck. He talks about 2006: the year he leased his land to Cabot Oil and Gas for $25 per acre. At the time, nobody thought natural gas drilling would ever take place in Dimock. Leasing was just a quick way to earn some badly needed cash. Next month’s mortgage. A new bike for the kids.

So when the drilling started last September and the enormous trucks bumped down Carter’s road and the night sky lit up like an industrial-strength Christmas tree, Carter and his wife Jean Carter were a bit surprised. They were even more surprised when they found out their water had been contaminated with fecal coliform — a bacterium often found in ground soil — sometime between July and November. The smell of it made Jean Carter sick to her stomach every time she tried to do dishes. It was undrinkable. Unusable.

The Carters took a sample to Cabot, which refused to pay for a water purification system. There are no materials used in natural gas drilling activities that use fecal coliform, according to Cabot. But the Carters believed that newly excavated access roads had flooded, spilling manure from a nearby pasture into their well. Carter, a 70-year-old ex-factory worker on disability, got a credit card and charged $7,000 for the system. He’s still paying it off, waiting for a royalty check for the gas taken on his land, from the same company he believes did the initial polluting.

Ken Komorowski, a Cabot spokesman, said he doubts the fecal coliform could have come from the drilling.

“Cabot does employ state-of-the-art erosion controls and meets all DEP requirements in regards to storm water flows,” he said. “That would include runoff from any construction activity.”

But the Carters’ water had never been contaminated before. Their neighbors across the field had never had such violent stomach pains, either. It all happened just a few months after the drilling started.

“I wish that they would have helped us with it when we had a problem with the water and not kept pushing us aside,” Carter said. “They wouldn’t help. We called them, I don’t know how many times.”

Fecal coliform was just the beginning. Not long after Carter had ordered his purification system, stories about a “methane scare” started creeping up the hill. Stories about well water that was orangey-brown or gritty enough to clog a washing machine.

Water that would ignite and burn for 11 minutes if you touched a match to it.

On Jan. 1, 2009, Norma Fiorentino, one of Carter’s neighbors, heard several loud bangs coming from her yard. Her well had exploded. Twenty-one days later, Cabot began providing drinking water to four Dimock households. The Carters didn’t get any, despite the fact that they had to install a vent over their well to sift out the excess gas.

“We were the guinea pigs in this area,” Carter said. He folded his hands and reclined, 7,000 feet above what geologists believe to be the third largest cache of natural gas in the world.

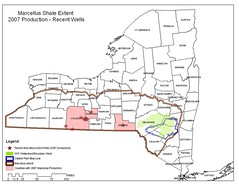

Carter, along with all of Dimock, sits atop the Marcellus Shale — a 31 million acre subterranean rock formation that runs under parts of Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, New York’s Southern Tier. If harvested to its projected potential — as much as 363 trillion cubic feet of gas, according to one Penn State geoscientist — the Marcellus’ reserve would be enough to heat the entire United States for two years. It could also generate billions in revenues and a flood of new jobs. But what has many citizens ... in an uproar is the potential environmental cost of drilling. As Dimock illustrates, it can be quite a messy endeavor.

... In order to access gas in the Marcellus, (hydrofracking) a well involves forcing between 2 and 9 million gallons of water, sand and chemicals down thousands of feet into the ground to break up rock formations and unleash gas. Around half of the water used stays in the ground. The other half — usually between 1 and 4 million gallons — emerges from the well and rests in man-made “disposal pits.” A well can be fracked up to 10 times during its productive life, generating between 10 million and 40 million gallons of wastewater.

“That water has to go somewhere,” said Steve Penningroth, a co-founder of the Community Science Institute, a nonprofit organization that helps monitor the Cayuga watershed.

“The thing is it’s not water. It’s like you’re taking 5 million gallons of fresh water, and you’re contaminating it intentionally. You’re leaving half of it in the ground, and then you’re looking for a place to dispose of the other half.”

Under any other circumstances, the water stored at disposal pits would be considered hazardous waste and aggressively regulated. But thanks to the Federal Energy Policy Act, a piece of legislation signed into law by the Bush administration in 2005, oil and gas companies are exempt from much of the Safe Drinking Water Act. This essentially means that the chemicals being shot into the ground — benzene, methanol, ethylene glycol, among others — get a free pass.

Curiously, these chemicals aren’t allowed anywhere near drinking water if used for purposes other than oil or gas exploration.

For complete article, CLICK HERE.

“The people they haven’t drilled near should be aware of what can happen with the water situation,” Carter said. “’Cause every place they’ve drilled, the water’s gone bad. It isn’t an isolated house here and a house there.”

He points down the gashed, mucky road.

“Every house has something wrong with their water.

I don’t know whether it’s going to go away.”

U.S. producers, loudest among them being Chesapeake (

U.S. producers, loudest among them being Chesapeake (