AlterNet

by Byard Duncan

July 30, 2010

Natural gas drilling operations have mucked up food from Colorado to Pennsylvania. So why is no one paying attention?

On the morning of May 5, 2010, nobody could say for sure how much fluid had leaked from the 650,000-gallon disposal pit near a natural gas drill pad in Shippen Township, Penn. -- not the employees on site; not the farmers who own the property; not the DEP rep who came to investigate.

But there were signs of trouble: Vegetation had died in a 30’ by 40’ patch of pasture nearby. A “wet area” of indeterminate toxicity had crept out about 200 feet, its puddles shimmering with an oily iridescence. And the cattle: 16 cows, four heifers and eight calves were all found near water containing the heavy metal strontium. Strontium is preferentially deposited in cows’ bones at varying levels depending on things like age and growth rates. Since slaughtering 28 cattle on mere suspicion can devastate a farmer financially, nobody knows what, if anything, the cows ingested. They're now sitting in quarantine.

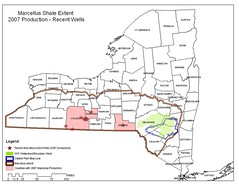

The Shippen Township incident isn’t the first time hydraulic fracturing, a controversial gas extraction technique that involves shooting water, sand and a mix of chemicals into the ground to release gas, has been blamed for livestock damage. But for farmers in the northeast whose land sits atop the gas-rich Marcellus Shale formation, it is a wake-up call – an event that raises questions about fracking’s compatibility with food production.

“I’ve already heard from a couple of customers that they’re concerned about the location of a drill site near my farm – in terms of the quality and safety of my food,” said Greg Swartz, a farmer in Pennsylvania’s Upper Delaware River Valley. Swartz, who sells all his products locally, fears that leaked fracking fluid could seep into his soil, bioaccumulate in his plants and cost him his organic certification. “There very well may be a point where I am not comfortable selling vegetables from the farm anymore because I’m concerned about water and air contamination issues,” he said.

Air contamination – specifically the production of ozone – is what worries Ken Jaffe, another farmer in Meredith, NY. When excess methane gas, coupled with volatile compounds like benzene, toluene and xylene, are released into the air in a process the gas industry calls “venting,” it can inhibit lung function and wreak havoc on plant life. In Sublette County, WY, fracking has been blamed for ozone levels that are comparable to those in Los Angeles.

Without healthy pasture, Jaffe said, his cows won’t grow. Which means his beef won’t sell. “The economics of my operation are in part based on how many animals I can graze per acre and get them to grow fat,” he told me. “And if I have less grass and less protein and less clover, then I have a problem.”

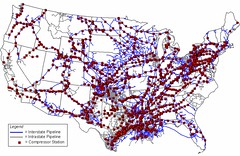

Over the past two years, horizontal hydraulic fracturing has garnered a lot of attention. Advocates of the practice believe the staggeringly high amounts of gas it makes accessible could serve as a “cleaner-burning” bridge between fossil fuels and renewable energy sources. But critics blame fracking for a whole range of problems -- house explosions, flammable drinking water, chronic sickness, crop failure and air contamination, to name a few. In 2005, the Bush administration introduced the Energy Policy Act, which exempted hydraulic fracturing from several key environmental regulations, including parts of the Clean Water Act and CERCLA (Superfund). Since then, drilling operations (along with corresponding environmental problems) have begun to extend like spiderwebs across states like Colorado, Wyoming, Texas, and Pennsylvania.

For all their concerns, farmers like Swartz and Jaffe comprise only one side of a larger debate over drilling. Leasing one’s land, after all, carries the promise of a comfortable retirement -- sometimes even millions of dollars. And with milk prices making small-scale dairy operations harder and harder to maintain, many farmers are looking for the light at the end of the pipeline.

Some have found it. According to one Penn State study, Pennsylvania made a $2.95 billion profit from drilling in 2008 alone; the state also gained 53,000 new jobs. And in the Windsor/Deposit area of New York, 300 property owners have signed a lease with XTO Energy that covers 37,000 acres and is worth $90 million (notably, the lease contains a provision that indemnifies drillers against damage to livestock). Though New York is still waiting on its Department of Environmental Conservation for the go-ahead to start horizontal drilling, much of the state’s topography has already been carved, cordoned and auctioned off to eager gas companies.

“The way things are now financially, it would be hard to turn [leasing] down,” said Richard Dirie, a dairy farmer near Youngsville, NY. “Farming is definitely a physical occupation. You definitely reach an age where -- I don’t care if you want to do it or not -- you just can’t do it anymore.”

Dirie has not yet leased his land. But at 59, he’s not sure he would reject an offer if it came his way. “I keep saying, ‘I hope they don’t come and talk to me.’ That way I don’t have to make a decision, you know?”

Gas drilling raises a lot of questions for farmers short on options. Is it worth the risk to retire comfortably? What are the implications for future use of the land? Perhaps most importantly: How does fracking affect crops, livestock and, by extension, the people who consume them? Answers are scarce.

“There’s a lot going on out there and we don’t know most of it,” Swartz said.

The Knowledge Vacuum

It’s with good reason that Jaffe describes fracking’s relationship to food as “a knowledge vacuum.” Pennsylvania’s Department of Agriculture can’t say for sure whether or not any cows in the state came into contact with fracking fluid before the Shippen Township incident in May. Nor can it guarantee similar things won’t happen in the future. “We hope that this is the exception rather than the rule,” said spokesman Justin Fleming. “We hope that this is an extraordinarily rare occurrence.”

A representative for the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service -- the organization in charge of testing milk and meat for chemicals – neglected to comment on whether or not heavy metals like the strontium found in Shippen Township were considered “adulterated” under the Federal Meat Inspection Act. He also did not immediately comment on whether naturally occurring radioactive materials (NORMS) -- known to surface after a well has been fractured – fall under the act’s clause banning meat from being “intentionally subjected to radiation.”

Scientists, too, are grappling for information. Though there exists an increasingly comprehensive catalog of knowledge about water problems related to fracking, little work has been done to determine how the practice affects animals and crops.

“I see very little research being done on cows,” said Theo Colborn, founder of the non-profit Endocrine Disruption Exchange. Because animal testing with many chemicals known to be involved in fracking has historically failed to deal with instances of a) limited exposure and b) prolonged exposure, no one really knows what the potential health effects are – for cows or humans.

“It’s very difficult to deal with this problem,” Colborn said. “Who has the money? Who can perform the tests?”

Certainly not the federal EPA. Earlier this year, it announced plans to launch a two-year study of hydraulic fracturing’s effects on water. According to an EPA spokesperson, no part of that study will deal with plants or animals.

And yet, there is significant anecdotal evidence that suggests fracking can seriously compromise food. In April 2009, 19 head of cattle dropped dead after ingesting an unknown substance near a gas drilling rig in northern Louisiana. Seven months before that, a tomato farmer in Avella, Penn. reported a series of problems with the water and soil on his property after drilling started: he found arsenic levels 2,600 times what is recommended, as well as dangerously high levels of benzene and naphthalene – all known fracking components. And in May 2009, one farmer in Clearview, Penn. told Reuters he thought that gas drilling operations had killed four of his cows.

Occurrences like these aren’t just limited to the eastern U.S. In Colorado, a veterinarian named Elizabeth Chandler has documented numerous fertility problems in livestock near active drill sites, including false pregnancy, smaller litters and stillbirths in goats; reduced birth rates in hogs; and delayed heat cycles in dogs.

In another case, Rick Roles, a resident of Rifle, Colorado, reported that his horses became sterile after three disposal pits were installed near his home. Like those in Chandler’s study, Roles’ goats began yielding fewer offspring and producing more stillbirths. Roles himself suffered from swelling of the hands, numbness and body pain – symptoms, he said, that subsided when he stopped eating vegetables from his garden and drinking his goats’ milk.

Actual scientific studies are few and far between, but what’s out there paints a pretty damning picture. One, titled “Livestock Poisoning from Oil Field Drilling Fluids, Muds and Additives,” appeared in the journal Veterinary & Human Toxicology in 1991. It examined seven instances where oil and gas wells had poisoned and/or killed livestock. In one such case, green liquid was found leaking from a tank near a gas well site. The study’s authors found 13 dead cows, whose “postmortem blood was chocolate-brown in color.” Poisoning cases involving carbon disulfide, turpentine, toluene, xylene, ethylene, and complex solvent mixtures “are frequently encountered,” the study concluded.

Another study, this one conducted in Alberta, Canada in 2001, investigated the effects of gas flaring on the reproductive systems of cattle near active gas and oil fields. Its conclusions: “One of the most consistent associations in the analysis was between exposure to sour gas flaring facilities [as opposed to “sweet” ones, which contain more aromatic hydrocarbons, aliphatic hydrocarbons and carbon particles] and an increased risk of stillbirth. In 3 of the 4 years studied, cumulative exposure to sour flares was associated with an increased risk of stillbirth.”

'Rare Cases'

When questioned about fracking and food, America’s Natural Gas Alliance, an organization composed of the nation’s leading gas production and exploration companies, neglected to get into any specifics. Instead, it offered this response:

“In rare cases where incidents have occurred,  companies have worked with the appropriate regulatory authority to identify, contain and correct the issue, and to implement measures to ensure they don’t recur. ANGA member companies understand and respect people’s concerns about the safety of their water and air, and we are committed to engaging in dialogue with community members, policymakers and stakeholders to talk about the safety of natural gas production and the opportunities natural gas offers communities across our country.”

companies have worked with the appropriate regulatory authority to identify, contain and correct the issue, and to implement measures to ensure they don’t recur. ANGA member companies understand and respect people’s concerns about the safety of their water and air, and we are committed to engaging in dialogue with community members, policymakers and stakeholders to talk about the safety of natural gas production and the opportunities natural gas offers communities across our country.”

Environmental groups have a markedly different perspective on the issue. “There’s a lot of violations that happen out there that are never documented,” said Wes Gillingham, program director of Catskill Mountainkeeper.

When we talked, Gillingham took out an enormous aerial photo of a drill rig. One disposal pit was surrounded by gray blotches of moisture: leaked fracking fluid. “The stuff that’s coming up – this stuff is getting into the environment,” he said, pointing at the blotches. “You’ve got heavy metals and normally occurring radioactive materials, all of which bioaccumulate in a grazer. That stuff is coming up in the grass where the grass is growing.”

So what sorts of concerns should people have about eating animals that have themselves ingested xylene, benzene, heavy metals, radioactive material? Gillingham, like so many farmers, federal officials and industry reps, can’t say for sure.

“It’s a serious issue in terms of potential contamination getting to market and nobody knowing about it,” he said. “It’s an important piece of research that needs to be done.”