November 27, 2009

NOT INTERESTED Lisa Wujnovich and her husband, Mark Dunau, refuse to sign a lease to allow natural gas drilling on their 50 farmland acres in Hancock, N.Y.

NOT INTERESTED Lisa Wujnovich and her husband, Mark Dunau, refuse to sign a lease to allow natural gas drilling on their 50 farmland acres in Hancock, N.Y. CHENANGO, N.Y. — Chris and Robert Lacey own 80 acres of idyllic upstate New York countryside, a place where they can fish for bass in their own pond, hike through white pines and chase deer away.

But the Laceys hope that, if all goes well, a natural gas wellhead will soon occupy this bucolic landscape.

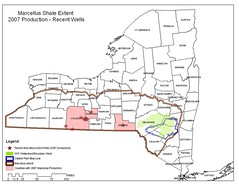

Like many landowners in Broome County, which includes the town of Chenango, the Laceys could potentially earn millions of dollars from the natural gas under their feet. They live above the Marcellus Shale, a subterranean layer of rock stretching from New York to Tennessee that is believed to be one of the biggest natural gas fields in the world.

As New York environmental officials draft regulations to allow drilling in the shale as early as next year, thousands of residents like the Laceys in upstate counties have banded together in coalitions to sign leases with gas companies for drilling on their land — for $5,000 to $6,000 an acre for a term of five years, and royalties of up to 20 percent on whatever gas is found.

“When I heard about drilling, what came to mind was ‘Thank you,’ ” said Mrs. Lacey, 58, who has lived on her property here for 27 years with her husband, Robert, 68, a commercial insurance agent. “Finally our community can recover, and our children don’t have to leave the state to find jobs.”

In New York City, natural gas exploration is largely seen as a threat to the drinking water the city gets from watersheds to the north in the Catskills. But in the rural communities above the shale, the reaction has been far more mixed — and far more contentious.

Some residents welcome the drilling as a modern-day gold rush and salvation from the economic doldrums that they say have chased jobs and young people away from their area. Others express concerns about the environment and quality-of-life issues like noise and heavy-truck traffic.

In some cases, the issue has pitted neighbor against neighbor or spouse against spouse.

Exploring the shale involves a drilling method called hydraulic fracturing that requires pumping huge volumes of water laced with benzene and other chemicals into the rock to break it and extract gas. The process raises issues about the use and disposal of wastewater, and the danger of leaks, spills and other contamination. It has been linked to contamination of water wells in Pennsylvania and Wyoming and to the death of livestock in Louisiana.

Mark Dunau, an organic vegetable farmer with 50 acres in the town of Hancock in Delaware County, says he is passing up any potential rewards from drilling because of worries about the pollution of water and air and the cumulative impact of thousands of wells. “That water is my resource,” he said.

Mr. Dunau, 57, and his wife, Lisa Wujnovich, 55, said that they were holdouts not only among their neighbors but also among their friends, and that the character of their community was already changing. Mr. Dunau said he knew people who said they would take the money and move away, families who were fighting over whether to sign gas leases, and neighbors who regretted signing too early for too little money.

“It’s a nightmare,” he said.

One of Mr. Dunau’s neighbors, Grace K. Kinzer, signed a lease with Chesapeake Energy two years ago when a representative of the company knocked on her door with an offer of $25 an acre and royalties of 12.5 percent, she said. Ms. Kinzer, 83, said she needed money to pay her taxes so she signed, getting about $2,750 for 110 acres that would now fetch more than half a million dollars.

...

...

Mr. Ernst, 72, favors drilling as a matter of survival. “We’re prostrate, and dependent on oil from enemy countries,” he said.

His wife, 74, said she was too worried about possible accidents and chemical spills.

“My main concern is the aquifer,” she said. “We have our own well. I don’t want to have to buy bottled drinking water.”

She refuses to sign a lease, and, after 46 years of marriage, Mr. Ernst said, he knows better than to think he can persuade her. “That’s like asking how do I plan to fly to Pluto,” he said.

But the holdouts cannot stop the transformation of their surroundings, both good and bad, once drilling is allowed. The area of the shale in New York that is expected to be the most productive spans about 3.4 million acres in 10 counties, but lies mostly in Broome, Delaware, Sullivan, Chenango and Tioga, said officials from the Independent Oil and Gas Association of New York.

Further fostering bad feelings within communities, under a concept known as “compulsory integration” gas companies can drill under land without the owner’s consent if they have leases in most of the surrounding area. Those owners without leases would get royalties of 12.5 percent on gas from their property, the minimum allowed under state law, but many worry more about exposing their water to pollution.

“They could be drilling directly under your well and threatening your groundwater,” said Wes Gillingham, the program director for the environmental group Catskill Mountainkeeper. He owns 100 acres in Sullivan County and said he was trying to keep it off-limits to drilling.

The regulations proposed by New York’s Department of Environmental Conservation are under fire as inadequate from environmentalists around the state. Another concern shared by both the pro- and anti-drilling sides is whether the environmental agency, which has suffered financial and staff cuts, will have the resources to monitor the drilling.

But the financial benefits beckon strongly in the communities that stand to benefit from a gas boom at a time when they are suffering economically. Broome County, which has lost jobs and population over the last decade, would stand to gain $3.72 billion a year in wages and tax and retail revenue from up to 4,000 gas wells, a study commissioned by local officials estimated. (However, a report by Columbia University researchers this year noted that any prediction of economic results was “entirely speculative” because of unknowns like the potential cost of cleaning up contamination.)

...

“We cannot afford to chase this industry away,” Patrick J. Brennan, deputy county executive, told state environmental officials this month at a hearing on the proposed rules governing drilling that drew about 800 people to a school auditorium in the county.

Both to poor residents with small parcels of land and wealthy landowners with vast estates, drilling represents an economic opportunity tantamount to winning the lottery. Jim Ward, who heads a landowners’ coalition with 138 members whose properties range in size from 650 acres to half an acre, said the sentiment in his group is: “I should have a right to prosper from my land.”

...To read the complete article, CLICK HERE.