November 01, 2009 5:59 AM

By Erik Engquist

“Water itself is toxic; there was a death three or four years ago from an overdose of water, as part of a radio contest,” says Brad Gill, executive director of the Independent Oil and Gas Association of New York and owner of a drilling company.

(Amazing...)

Jeff Decker used to scratch out a living as a truck driver, inching his rig down the Cross Bronx Expressway and rolling across lonely interstates. He built a small trucking business, then sold it, but the proceeds were eaten up by basic expenses and the stock market. The 47-year-old makes ends meet by doing odd jobs and farming on the 120 rural acres outside Binghamton, N.Y., he inherited from his father, who began cobbling together parcels back in 1958.

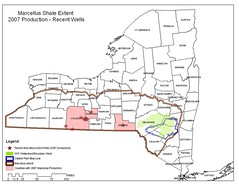

Never did Mr. Decker imagine that his property was perched atop a figurative gold mine: a 95,000-square-mile, $1 trillion deposit of natural gas trapped within the rock of the Marcellus Shale formation—enough to supply the nation for 20 years. And neither he nor anyone else in the long-suffering Appalachian Mountains region anticipated that a frenzied quest to extract the fuel would spawn hope and havoc, dividing communities on whether it'll be a boon or a boondoggle.

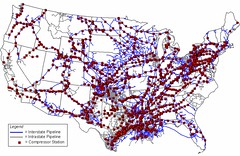

Natural gas drilling is exploding—sometimes literally—across the border in Pennsylvania. In New York the Paterson administration, heeding the cries of landowners and local officials in economically depressed upstate communities, has issued draft regulations to allow it here. Landowners are keen to lease their property. Cash-strapped municipalities are eager to tax the extracted gas. Business groups say drilling would bring jobs and jolt local economies. The state would collect more income tax and, if it imposes one, a tax on gas production.

But drilling poses risks. A New York City analysis has concluded that every aspect of drilling threatens Gotham's drinking water, so the Bloomberg administration and elected officials want the activity banned in the upstate watershed, which occupies 8.5% of New York's portion of the Marcellus Shale. New York is one of five big cities not required by the federal government to filter its water, and revocation of that waiver would necessitate a filtration plant costing $10 billion to $20 billion.

...

The world is quickly waking up to the immense economic ramifications of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, or hydrofracking. Shale deposits—called plays—across the globe have the extraction industry in a feeding frenzy, and the massive Marcellus, one of several plays sprawling into New York, may be the hottest property of all. Only two years ago, the energy companies' “land men” were offering landowners in places like Broome County, where Mr. Decker lives, $50 an acre for drilling rights. Today, it's $5,750.

“The next Jed Clampett?”

... Mr. Decker, who rejected the land men's initial offers of $6,000 or so, is closing in on a deal. The Vestal coalition's lawyer won't let Mr. Decker divulge the terms, but the going rate would mean a signing bonus approaching $700,000.That pales in comparison to what he might reap once the gas starts flowing. An 80-acre swath of the Marcellus can eventually produce $42 million worth of natural gas, says Dean Lowry, president of Fort Worth, Texas-based Llama Horizontal Drilling Technologies. With drilling leases now giving landowners 20% royalties on productive wells, Mr. Decker could become a millionaire several times over.

...

Pat Farnelli sees the effects on a daily—and nightly—basis. The mother of eight and four-year resident of Dimock, Pa., emerges breathless from her cramped farmhouse with a stack of papers and a digital camera, which she promptly drops on the lawn. She apologizes for her frantic manner. Asked if it is drilling-related, she seems surprised by the question: “Nothing happens in Dimock that isn't drilling-related anymore.”

Two years ago, the land men signed up the Farnellis and everyone else on unpaved Carter Road for $25 an acre plus Pennsylvania's statutory minimum of 12.5% royalties. There was little chance they'd ever drill, Ms. Farnelli recalls them saying, but if they did, at most they'd do one well every 640 acres. “They made it sound like a nice little windfall,” she says.

The landowners, many of whom work in the moribund quarry industry, considered it found money. None consulted a lawyer. “This entire road was in a state of desperation,” she explains.

Now, desperation truly is at hand. “For the last year and a half, they've been drilling and fracking around my house constantly,” Ms. Farnelli says. At night, stadium lights from a dozen drill sites flood her daughter's bedroom, and workers chatter on walkie-talkies. The fracking shakes her old house, and blasting is common. “I don't even flinch anymore,” Ms. Farnelli says as an explosion reverberates across the landscape.

Trucks rumble by every few minutes. Carter Road was too narrow for them, so the driller widened it—chopping off the edge of Ms. Farnelli's lawn. “Never asked us,” she says. “We had flower beds there.” Earthmovers changed the pitch of the hayfield above her house; now the road and her driveway wash out when it rains.

Methane in the water wells

Carter Road's biggest problem is the drinking water. One water well after another filled with sediment, methane and unknown elements. Ms. Farnelli's family suffered from intestinal sickness for months before fingering their tap water as the culprit. Pour a neighbor's water into a glass, she says, and it separates into sludge, sediment, brown liquid and bubbles; another's smells like formaldehyde. Ms. Farnelli says drilling-company testers found methane seeping into her well and basement.

Last New Year's Day, neighbor Norma Fiorentino's water well blew up. A spark from the pump might have ignited methane that, freed by drilling, had migrated underground. Blocks of concrete were blown across the yard. The driller refused to provide bottled water until last week, when a Scranton newspaper splashed the story across its front page. Says Ms. Farnelli, “We're basically ruined.”

...

The gas industry maintains that hydrofracking has not contaminated a single drop of drinking water. Comparing the heavy metals and other chemicals in fracking fluid to canola oil, shampoo and chlorine, industry leaders object when the substances are described as toxic.

“Water itself is toxic; there was a death three or four years ago from an overdose of water, as part of a radio contest,” says Brad Gill, executive director of the Independent Oil and Gas Association of New York and owner of a drilling company. “The key is concentration and exposure. Most of these chemicals are benign.”

The Bloomberg administration and a coalition of environmental and civic groups insist otherwise. They're lobbying the state to drop its plan to allow hydrofracking in the upstate areas that supply unfiltered water to 9.1 million people downstate. Drilling opponents won a big victory last week when Chesapeake said it would not drill in the city's watershed, given the headaches it would involve and the ready availability of the other 91.5% of the Marcellus Shale.

Chesapeake's announcement took some pressure off the Paterson administration but could empower advocates who are demanding protection for other watersheds.

The state regulations proposed Sept. 30 are considered among the nation's strongest. But they might not go far enough, says Kate Sinding, an attorney for the Natural Resources Defense Council. Among her questions: How will leftover hydrofracking fluid be disposed of? Shouldn't its chemical contents be made public? Does the state have enough staff for enforcement? “We're going to look at what the risks are and insist they get managed to the maximum extent possible,” she says.

For the complete report, CLICK HERE.

Editorial comments by Splashdown in red.

No comments:

Post a Comment