There's no question that the recent boom in Marcellus Shale gas drilling has put money in the coffers of small towns across Pennsylvania -- but in the words of Dr. Conrad Volz, at what price? "This is a potentially huge public health problem," said Volz, of the University of Pittsburgh's Graduate School of Public Health. Under normal circumstances, Volz does not talk in alarmed sound bites. But Volz said these are not normal circumstances.

Jenny Smitsky, who lives in Hickory, Washington County (about 25 miles from Pittsburgh, PA) lost three goats and all the fish in her pond. In fact, the EPA told her not to use her well water for any purpose, even washing. Testing revealed very high levels of manganese -- 100 times the acceptable amount -- in her well water. Her home is surrounded by gas wells.

"I had good, clear, good-tasting water. I never had a problem until drilling started," Smitsky said.

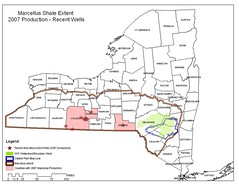

Volz said contaminated waste water from Marcellus drilling will have an impact on all of us, since it is being discharged into the Monongahela River. "The total dissolved solid levels are going up. These problems are occurring in our main stem river, where most of the population is getting their water," Volz said. "This just doesn't make sense, and it is a moral and ethical problem." Department of Environmental Protection spokeswoman Helen Humphreys said her agency is not convinced that the elevated levels of manganese in Smitsky's water were caused by Marcellus Shale drilling. The DEP plans to test Smitsky's water again.Trillions of cubic feet of natural gas are locked under the Marcellus Shale that runs from West Virginia, through Ohio, across most of Pennsylvania and into the Southern Tier of New York state. It takes an estimated 3 million to 5 million gallons of water per well to drill down to the natural gas in a process called hydraulic fracturing, or fracking. The water is mixed with resin-coated sand and a cocktail of hazardous chemicals, including hydrochloric acid, nitrogen, biocides, surfactants, friction reducers and benzene to facilitate the fracturing of the shale to extract the gas.

About 60 percent of the toxic water used to extract the natural gas is left underground to seep into surrounding ground water. According to Celcias, farm animals that have drunk this have died. Cattle ranchers in Colorado have reported that their livestock birthrates have gone down and animals are bearing deformed offspring.

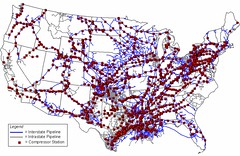

In other words, communities that live down stream and that depend on water from our rivers should be keeping an eye on the water quality. We all want cheap energy sources, but without clean water, nothing will survive. These wells often spring up in areas where cows graze. If we poison our food supply, we will be poisoning ourselves, too.

To read more CLICK HERE and HERE.

No comments:

Post a Comment