Published: October 26, 2009

thetimes-tribune.com

DIMOCK TWP.

The problem in the water here erupted on New Year's Day when an explosion in Norma Fiorentino's backyard well shattered an 8-foot concrete slab and tossed the pieces onto her lawn.

An investigation by the state Department of Environmental Protection revealed that the culprit - methane in the aquifer because of nearby natural-gas drilling - had seeped into the drinking water at nine homes in the township, causing a threat of explosion in at least four of them.

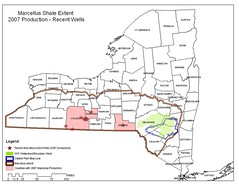

The department found that Cabot Oil and Gas Corp., the company that had drilled 20 wells into the gas-rich Marcellus Shale within three square miles of the blast, had polluted the fresh groundwater with methane, the highly combustible, primary element of natural gas. Inspectors suspected that too much pressure in the mile-deep wells or flaws in their cement-and-steel casings had opened a channel for the gas.

Now, the state environmental oversight agency is rethinking its gas drilling regulations with the aim of preventing incidents like the one in Dimock from happening again.

An early draft of regulations the department unveiled in September would change the way wells are built and sealed off from drinking water aquifers; mandate that existing wells are tested to ensure they don't leak; increase cementing and casing standards and strengthen rules for replacing drinking water if gas drillers disturb it.

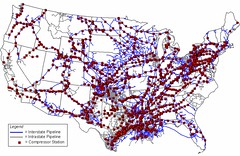

Rising fast

Now that the state is poised to become one of the biggest gas producers in the nation, "we want to make sure that we're putting in place for Pennsylvania and for the public over the next 50 years the very best practices and the best materials in our regulations," DEP Secretary John Hanger said.

Although Mr. Hanger said the proposed regulations were not inspired by any particular incident, catastrophes or close calls caused by stray gas migrating from natural gas wells "highlight the reasons for the review and the changes." A cover letter from DEP to the state's Oil and Gas Technical Advisory Board made the case in stark detail: Over the last decade, six explosions caused by gas that migrated from new or old wells killed four people in the state and injured three others. The threat of explosions has forced 20 families from their homes, sometimes for months, and at least 60 water wells, including three municipal water supplies, have been contaminated.

...

To tap the gas-bearing rock, a well bore must penetrate several geological layers before reaching the target formation; in the case of the Marcellus Shale, it is often about a mile underground. The hole is then sealed off from the drinking water aquifer and the surrounding geology with several rings of steel casing, which keeps the gas and the chemical-laden liquid used to fracture the shale from seeping out and helps control the tremendous pressure that builds up inside the well. In particularly sensitive areas, like groundwater zones, the casing is cemented into place to make sure the barrier is impermeable.

According to a report by the Ground Water Protection Council, a coalition of state water regulators from around the country, casing is a crucial protection for groundwater, but it is the cementing of the casing "that adds the most value to the process of groundwater protection." Because of that, the quality of the initial cement job "is the most critical factor" in preventing gas and fluids from getting into the drinking water supply.

Stronger safeguards

The DEP's proposed rules would strengthen that standard of protection. For the first time, oversight would be added to ensure that cement completely surrounds the surface casing - the steel pipe most responsible for protecting drinking water - and call for deeper casings to be cemented above any gas-producing rock layers.

The rules would mandate that companies create a casing and cementing plan before each well is drilled, outlining the type and strength of casing and cement to be used and more fully incorporating national standards for the cement and pipe. They would also create an annual reporting requirement for companies to inspect every operating well to make sure there is no obvious leak, corrosion or excess pressure.

In addition to changes in the way wells are built and inspected, the new rules would establish clearer standards for what gas operators must do to restore or replace residents' water supplies if their drilling pollutes it. An "adequate" replacement would now have to be as reliable, accessible, clean, plentiful and permanent as a resident's previous, untainted supply, and it could not cost more to maintain. If residents tell a gas operator that their water has been polluted, the company would have to report the complaint to DEP.

Mr. Hanger said the department is proposing to strengthen the response for when somebody loses their drinking water because he has "not been fully satisfied" with the way polluted supplies are being replaced under the current standard.

Standard of living

Norma Fiorentino has not consumed water from her faucets since her well exploded 10 months ago. The 66-year-old widow lugged jugs of it up a hill from her neighbors' house for about a month, until they found out they had methane in their water, too. Now she buys it for about $20 a week at the grocery store or travels to a spring in Montrose to collect it.

Cabot has been providing water to four families since January and has installed methane separation systems in the basements of three homes, according to Kenneth Komoroski, a Cabot lawyer and spokesman. DEP puts the count higher, saying Cabot is providing water or treatment systems to 13 Dimock homes with elevated methane.

But residents say at least 18 families no longer drink their well water, many of whom, like Mrs. Fiorentino, pay for replacement water on their own.

"I've begged him since my well blew up to give me water," Mrs. Fiorentino said of Mr. Komoroski, "but he's never given me a bottle."

In the middle of September, a group of Dimock landowners met with Cabot representatives to plead for water supplies to replace the wells they believe have been contaminated. They have observed odd changes: bubbling from the methane, but also odors, foam, an orange color or shimmering white flakes. Water tests at their homes have revealed elevated levels of iron, aluminum and bacteria as well as methane.

A DEP investigation in March found that hydraulic fracturing fluids from the Cabot gas wells had not contaminated the water in the homes affected by the methane migration, but residents continue to have concerns.

"Most of us believe methane is the least of our worries," Victoria Switzer, the meeting organizer, said. "We'll never drink our water."

Plugging leaks

... both Cabot and DEP are continuing their investigations into what is causing the stray methane. Stable isotopes in the methane dissolved in the water, which Mr. Baldassare, the DEP stray gas inspector, likens to a genetic fingerprint of the gas, have allowed them to determine that the gas originated not from the Marcellus, but from another Devonian shale formation above the Marcellus.

DEP spokeswoman Freda Tarbell said the department knows the gas came from a Cabot well "but we don't know how it got there or why." Cabot insists DEP was premature in announcing that the company was responsible for polluting the water supply.

...Mr. Komoroski said Cabot will produce a final report in less than 60 days that will "attempt to rule in or rule out Cabot as a cause or a contributing source."

But Mr. Baldassare, who has reviewed Cabot's preliminary report, said the company report provides "no evidence whatsoever" that the gas in the water came from anywhere but one of its wells.

Although the lessons of past well drilling mistakes are helping to shape the state's new regulatory direction, Mr. Hanger faces an uphill battle to turn the proposed rules into law.

Risk mitigation

In DEP's cover letter to the technical advisory board, the department acknowledged that "controversy may ensue" from the introduction of the proposed regulations. Already the new rules have been met with skepticism by the industry and caution by the advisory board members.

"We all understand the goal of course," said Stephen Rhoads, the president of the Pennsylvania Oil and Gas Association.

But he said there are clearly "issues" with the proposed casing and cementing requirements and the well monitoring plan, and the industry will be giving all of the proposals a thorough review to make sure they are "technically sufficient."

...

Loss and gain

In Dimock, Ms. Switzer was ready to weigh in on the proposed regulations: She would like to see all of Cabot's earliest gas wells inspected.

For the last five years, she and her husband have been living in a cramped trailer in a gully near Burdock Creek as they build their retirement home, an investment that has wedded them to the town and the drilling.

She pointed to a recess in the wall during a tour through her future kitchen. "This was going to be our wine closet," she said. "Instead, this is where we'll put our water."

The unofficial leader of the local residents' fight for safe gas extraction, Mrs. Switzer knows she is not popular.

In the best-case scenario, she said, she and her neighbors will have their water replaced and "everyone else will benefit from the tragedy of Dimock." The proposed DEP regulations have brought her some hope for that.

The alternative - "that we lost and no one gained" - would be too much to handle, she said.

"If people don't learn from this, then we are a total waste."

For the complete article, CLICK HERE.

DEMAND ACCOUNTABILITY!

ooo I bet she would!

ReplyDelete