by Candace Mingis offers up lots to think about.

It is reprinted with permission from the author.

Thank you Candace!

In 1971, when my husband’s family bought its farm in Van Etten, there was an abandoned Oriskany formation well on the property. There were, indeed, abandoned wells all over the neighboring hills — some of which were providing neighbors with free gas.

A small pipe and tank seemed innocuous enough. So when a neighbor came by in 1999 with his friend, an oil and gasman who owned a small company in Pennsylvania, we signed a ten-year lease.

It was a community-held belief in Van Etten, based on past experience, that gas wells were “no big deal.” Nearly all our neighbors signed. There were no informational forums back then, nor attorneys who knew what was coming.

Five years later, after the lower rights to our lease were assigned to a multinational corporation, we realized something bigger was happening and finally sought an attorney’s help. The first attorney we saw was knowledgeable but was interested in helping us only if we exercised a sale clause we had put in the lease, and sell our land to a friend of his who invested in oil and gas. His fee would be 33% of the additional royalties gained from the transaction.We were not comfortable with this.

The second attorney willingly assisted us with the high-pressure, eleventh-hour negotiations with the gas company, which now wanted to drill a well on our farm. But it soon became clear he knew nothing about the industrial gas drilling coming. Finding a reliable attorney was nearly an impossible task. We didn’t even know what questions to ask.

We scrambled to come up with last-minute protections, mostly from bits and pieces of information we were now learning from neighbors.

The gas company was willing to negotiate, as they had not yet gotten us to sign an amending agreement they needed. We forged an agreement to make sure our beautiful, gravelly loam field would be restored.

The well was drilled in the Trenton/ Black River formation. It was a conventional well that went nearly two miles down and one mile horizontally under the village. It was a huge industrial operation — a far cry from the old Oriskany wells on our hill.

From day one, the gas company began to cut corners. What was to be “just a couple of acres” was actually seven acres (we measured it.) We asked that the access road run along the edge of the field, and they cut it diagonally through the field. The landman who had been negotiating with us had actually helped us flag where the road was to be, and he argued for us to get them to re-do the road. It just went on and on. The holding ponds were supposed to have two layers of plastic. They had only one. The brine was supposed to be hauled out more often than it was. We felt we had to constantly be checking, taking pictures, and calling the gas company.

Of course, the operation was an industrial site we never could have imagined: 24-hour-a-day drilling, ramming noise, lit up all night. It went longer than they said it would, taking three months to prepare the site and drill. When the well was flared (for three days and nights) and the whole valley was lit up like a stadium, it began to feel like something terrible had been unleashed.

When it was time to restore the larger/outer area of the well site, the gas company cut corners once again, even though the procedure was spelled out clearly in the written agreement. They used a bulldozer to remove the plastic and large rocks, hauling much of our precious topsoil with it. My husband furiously tried to get them to stop, and subsequently to bring us more topsoil to fill in the depressions. Rude employees argued with him. They also never loosened the subsoil before filling in.

We had a retired Ag & Markets consultant come in and shoot some grades and write a recommendation. This appeared to really annoy the gas company.

They sent us a “without prejudice” letter stating they had done all they had to do until final restoration (10 years or so hence). The “friendly” landman who had worked on our behalf was told to stop talking to us.

We then knew that if we ever wanted to have that field restored as per the signed agreement, we would have to get an attorney. Attorneys tell us now that only rarely can you get industry to pay for your legal fees.

Having a multinational corporation in your life is extremely stressful. It’s a “contractual relationship,” but it is vastly unequal. Corporations are protected under the law, and are ultimately not liable, responsible or responsive. Their sole job is to make money for their shareholders, and they will do what they want. Oil and gas companies are essentially in the game of “gotcha!” Once you sign, it’s up to you to watch them, call them, sue them. It’s your problem now. They are obliging only until they get what they want from you. Phone calls, e-mails, letters, lawyers all become routine.

Signing a lease with a multinational corporation is like inviting a very rude, unscrupulous, uncaring (dare I say criminal?) person to live in your home. It is extremely stressful. However, this well, we were assured, would have a lifetime of only about 10 years, and then they would be “out of there—all cleaned up, like [we] didn’t know [they] had been there.” We thought we could live with that. (Of course, at this point we had no choice.) At this time our daughter and her husband decided to go ahead and make plans to move their farm/ winery business to the family farm.

And we were “lucky” ones. The well was successful. In fact, it was the most prolific well in New York, and in 2006 produced 4 billion cubic feet of gas — enough to heat 57,000 homes for a year. Organizations and 133 families receive royalties from this well, including the town, school and church. Who couldn’t use more money? Folks could finally repaint their houses and replace roofs. They could start retirement savings and donate to charities. We were able to finish our house and install solar panels, buy a tractor and pay off some college loans.

There is no denying that the people could use the money. But the question began to emerge: at what cost?

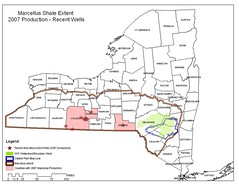

In the spring of 2008, we began hearing talk of the next big gas “play” — the Marcellus shale — and, at first, thought nothing of it. But the more we learned, the more alarmed we became, and then it hit us: we were “held by production” with a producing well, and that meant that lease expiration was irrelevant. And while we are held by production, more wells may be drilled on our property in different formations, which in turn could hold us by production longer.

In essence, we had “sold” our land forever. The night I realized this, I had a dream that our house had been robbed, and it was from the inside.

Now, our daughter seriously doubted they could move to the farm. How could they move here when there could be a lifetime of drilling, drastic change in our rural landscape, and potential contamination and pollution? We had “sold” the land out from under our children and their children. No amount of money is worth that.

Unconventional shale gas drilling is a nasty business. And I venture to guess there are hundreds, maybe thousands of leased-landowners out there who, as they learn what this new gas drilling really entails, wish they had never signed a lease.

A contract between an individual and a multinational corporation is never on an even playing field. The power imbalance is staggering. Attorney Jane Welsh, of Hamilton, believes gas leases should actually be commercial lease transactions, which include the legal concepts and protections found in any commercial lease, and “the only reason they are not is that the parties to a gas lease are woefully mismatched in terms of negotiating power, experience, sophistication and financial clout.” New York, she concludes, is sorely remiss in not regulating these leases.

But this is not merely a leasing issue (though the Attorney General’s Office, Cooperative Extension and many landowner coalitions seem to believe it is).

For one, it’s a community issue. As Herb Engman, Ithaca town supervisor, said recently (and I’m paraphrasing): Towns go through all the time, trouble and expense to generate comprehensive plans and protect community resources, and then gas companies can destroy all planning.

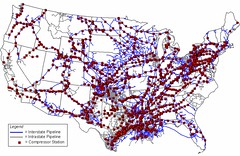

The scale of proposed shale gas drilling in the area will affect our entire landscape and rural way of life.

Leases cannot protect us from plummeting real estate values or the inability to obtain mortgages or sell our property; leases cannot protect us from a decline in tourism or other negative economic effects; leases cannot protect us from the increased difficulty in obtaining insurance or the increased cost of doing so. And unless gas companies are willing to post billions of dollars in bonds, leases cannot ultimately protect us from personal liability.

But above all, this is a public health issue. Emerging studies on air pollution and reports of water contamination make it very clear that the negative affects of unconventional gas drilling cannot be contained by property boundaries.

Whether you are leased, leased in a coalition or compulsorily integrated; whether you are un-leased living down the road, downwind or downstream of gas wells or deep injection disposal wells; or whether you simply use roads traveled by frack-water trucks — we are all at increased risk.

Our communities need full disclosure of the risks we will be exposed to before we can decide if we, as a community, want to take those risks. We do not want to be unwilling participants in a grand experiment, because that’s what this is.

And the truth is, no one even knows what all the risks are.

There have been no comprehensive, long-term, systematic studies of hydrofracking. Nor have there been comprehensive, long-term, systematic studies on deep injection disposal of toxic wastewater. But the high-pressure injection of contaminants into the ground appears to be liinked to unpredictable migration of fluids, aquifer contamination and possibly earthquakes.

Have we mapped our entire area for natural faults? How do we know that the fracking fluid left behind won’t eventually migrate upward and contaminate our water? Maybe not this year, but what about in five years or 50 years? While the gas companies and the DEC assure us that these activities are perfectly safe, they will not guarantee it, because there is no science backing those claims. And in fact, more and more evidence is mounting to the contrary —at the expense of people’s health and safety.

I am haunted by the specter of some day turning on my tap for a glass of our clear, cold, sweet water and wondering if chemicals left underneath us have migrated into it.

Do I test my drinking water once a year? Once a month? Every week? How can I live (how can we live) with the unending uncertainty that this glassful might be poisoned?

Do I drink it?

Do I offer it to my granddaughter?

No comments:

Post a Comment