Published: June 22, 2010

Range Resources dug a pit the size of a football field in the grassy acres just beyond June Chappel's property line last year, yards from the pen where she keeps her beagles and past the trees that shade the porch on her family's small southwestern Pennsylvania home.

Range Resources dug a pit the size of a football field in the grassy acres just beyond June Chappel's property line last year, yards from the pen where she keeps her beagles and past the trees that shade the porch on her family's small southwestern Pennsylvania home.

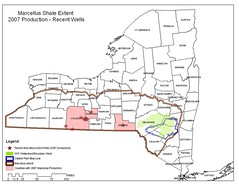

Range used it, at first, to store the fresh water needed to produce gas from the seven Marcellus Shale natural gas wells it drilled next door.

But when the company began to fill it with the salt- and metals-laden waste fluids that came back up from the wells, Chappel found odors like that of gasoline and kerosene forced her inside. The rising dew left a greasy film on her windows, she said, and one November day a white dust fell over the yard.

Resources:

DEP gas drilling violations databaseSearch natural gas leases in our online database

Complete coverage of natural gas drilling

She called the company to complain about the smell and workers came to skim booms across the pit, sopping up odor-causing residue and bacteria.

Throughout all of it, her husband, David, was inside the house, sick with and later dying of cancer at age 54.

"We've gone without," she said in January, standing by the pit with a hood over her head and her beagles nearby in coats. "We don't have a lot here. Now, I feel like it's ruined."

Like the wastewater pits increasingly used by the gas industry in Pennsylvania - the largest of which can hold the equivalent of 22 Olympic-size swimming pools full of contaminated fluid - the problem of what to do with the liquid waste from Marcellus Shale drilling is enormous.

The average Marcellus Shale well requires 4 million gallons of water mixed with sand and chemicals to break apart - or hydraulically fracture - the rock formation and release the gas.

About 1 million gallons of that fluid, now saturated with the salts, metals and naturally occurring radiation that had been trapped in the shale, returns to the surface to be treated, diluted, reused or pumped underground in deep disposal wells.

There has been significant progress in determining what exactly is in the waste and how to reuse it over the last two years - from when the state's environmental regulatory agency belatedly discovered that drillers were sending the fluids to publicly owned sewer systems incapable of treating it, to last week, when the state Independent Regulatory Review Commission endorsed strict restrictions on how much of the waste can be discharged into Pennsylvania's streams.

There has also been a surge in entrepreneurial activity from companies proposing to treat the waste, which can be up to 10 times saltier than sea water.

...But even as the state tries to push the stricter treatment standards into law, there are not enough treatment plants in Pennsylvania to remove the salt from the more than a half-million gallons of wastewater that is produced from Marcellus Shale drilling every day.

Those challenges raise what Conrad Dan Volz, director of the Center for Healthy Environments and Communities at the University of Pittsburgh, said is the most obvious of the unanswered questions about the current scale of Marcellus Shale gas production in the state: "Why would we ever start doing this drilling in this kind of intensive way if we didn't have some way to handle and properly dispose of the brine waters?"

Promise and problems with recycling

The problematic pit behind Chappel's home was also part of a pioneering development in the early life of Marcellus Shale gas extraction.

In October, Range Resources was the first company in the commonwealth to claim to be able to reuse all of the waste that flowed back from a well after it was hydraulically fractured. Using the pits, called centralized impoundments, Range discovered that it could dilute Marcellus Shale wastewater with fresh water and reuse it in the next well.

The seemingly simple solution had a dramatic impact: As Range doubled the number of gas wells it drilled between 2008 and 2009, it cut the amount of water it needed to discharge in half because of its reuse program, a spokesman said.

The company shared the information with the other Marcellus operators, and now 60 percent of the wastewater produced in the state is being reused, according to the Marcellus Shale Coalition, a cooperative of the state's Marcellus drillers.

But recycling alone will not cure the industry of a need to dispose of the waste.

In defining the need for strict discharge rules for Marcellus Shale wastewater in April, the Department of Environmental Protection wrote that even with recycling and reuse, "it is clear that the future wastewater return flows and treatment needs will be substantial."

Because the gas development is so new, it is still unclear how much wastewater will be created immediately and over time by the 50,000 new wells that are expected to be drilled in the next two decades.

The waste that flows back slowly and continuously over the 20- to 30-year life of each gas well could produce 27 tons of salt per year, the department wrote. "Multiply this amount by tens of thousands of Marcellus gas wells, and the potential pollutional effects ... are tremendous."

Recycling using centralized pits also has its downsides, from the intrusive to the dangerous:

- Chappel and her neighbors lived with the noxious odors from the pit behind their homes until they hired an attorney and Range agreed to remove it.

- Two of the Marcellus Shale violations for which Range has been cited and fined by the DEP have been for failures of the lines that transfer the waste fluids, sometimes up to seven miles between a wastewater pit and a well site.

- And the potential for the pits to emit chemicals or hazardous elements called volatile organic compounds into the air has been cited in studies in other states and is being monitored by DEP at sites throughout Washington County.

Matt Pitzarella, a Range Resources spokesman, admitted the decision to put the pit behind Chappel's house was "not a good choice" and the company has worked hard to correct it, including removing the pit, reclaiming the hill and even painting Chappel's house.

The company's eight or nine other impoundments in Washington County were built for longer-term use, he said, in areas farther away from people's homes.

Another Range spokesman at an April meeting with neighbors upset about the pit's smells said the impoundments hold "a lot of hydrocarbons," brine, and bacteria "from the water just sitting out there" and that can create odors.

"The warmer it gets, the more putrid it's going to get," he said.

The smell is "not dangerous or harmful. It's annoying."

But complaints of odors from pits helped spur DEP to conduct an air quality study around gas well sites in the region that is expected to be completed this month.

And in its review of the environmental implications of Marcellus Shale gas drilling, New York state determined that the threat posed by the pits may go far beyond annoyance.

An environmental impact statement under review there describes a "worst case scenario" for hazardous air pollutants - especially methanol used by drillers in fracturing fluids and as an antifreeze - escaping from large wastewater impoundments.

According to the report, a centralized impoundment that holds the wastewater from 10 wells could theoretically release 32.5 tons of methanol into the air each year - meaning it could qualify as a "major" source of toxic air pollutants under federal rules.

Because of the risk of leaks and other failures, New York also proposed to ban the use of such centralized impoundments within the boundaries of its most productive aquifers, which underlie about 15 percent of the state.

Broken pipes

The sheer volume of the wastewater and the number of trucks, pits, pipes and people necessary to move it over often long distances, has also increased the probability of leaks and spills, which have already occurred in Pennsylvania. Accidents described in DEP documents reviewed by The Times-Tribune show that the above-ground lines used to pipe the wastewater to and from impoundments and tanks are susceptible to leaks, even when companies take care to prevent them.

In October, an elbow joint came unglued in a PVC line carrying diluted wastewater from one of Range's pits and spilled about 10,500 gallons into a high-quality stream, killing about 170 small fish and salamanders.

According to Range, the company successfully tested the line with fresh water in the week before the wastewater transfer to make sure it could hold the pressure. It was the second transfer line failure for the company in five months.

In a separate incident, a water transfer line used by Chesapeake Appalachia in Bradford County failed five times in five places over five days in December. On one occasion, the pipe burst where it had been weakened from being dragged on the ground. Another time it failed because of a faulty weld, and another because bolts were loose on a valve.

In correspondence with DEP, Chesapeake said it was its policy to transfer only fresh water in its above-ground lines and to use only a more expensive "fused poly pipe" to minimize the risk of spills.

But an estimated 67,000 total gallons of the water did spill and DEP tests of the water found that it was not fresh. Instead, it had elevated levels of salts, barium and strontium - indicators of Marcellus wastewater that the company suspected may have mixed with its fresh water in one of its contractor's tanks, which may have been improperly cleaned between uses.

Brian Grove, Chesapeake's director of corporate development, said the incident did not pose a threat to the public and it did not result in any negative environmental impact. The company has since adopted new procedures for handling, storing and transporting water, he said, and held a meeting with all of its employees and contractors to reiterate its "commitment to safety and environmental stewardship."

Scott Perry, the director of the Department of Environmental Protection's Oil and Gas Bureau, said the above-ground pipelines might be addressed in upcoming revisions to the state's oil and gas regulations, which may also include an evaluation of the construction standards for centralized impoundments and other elements of the industry's handling of wastewater.

The current regulatory standard for the pipelines is that they cannot leak, he said.

"Maybe that's good enough," he said. "There's an absolute prohibition against getting a single drop of it on the ground."

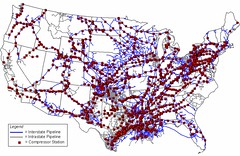

He emphasized that the regulatory agency has to find a way to permit the pipelines so it both protects the environment and encourages their use in order to remove excessive truck traffic from rural roads.

"In a practical sense, if you want to eliminate 100,000 trucks, this is the way to do it," he said.

Radisav Vidic, chairman of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the University of Pittsburgh, said a better way to minimize the risk of environmental damage is for companies to stop moving the wastewater so much.

Current industry practice for recycling the waste is to fracture a well and then drive or pipe the water to an impoundment or tanks, over and over, he said, "until they move 6 million gallons of water back and forth" to fracture multiple wells on one pad, creating an opportunity for spills with each trip.

Dr. Vidic is studying how to take the wastewater from one well, mix it with acid mine drainage, and use it to fracture subsequent wells on the same multi-well pad - research that is being funded in part by a grant from the U.S. Department of Energy.

He has found that the sulfates in acid mine drainage - one of the biggest sources of pollution in current and former coal mining regions of the state - interact with problem metals like barium and strontium in the wastewater and turn them into solids that can be discarded.

An obstacle to research, though, is how little some gas companies are willing to collaborate, both with him and each other to solve the wastewater problem, he said.

"Every company thinks they know it best, and they keep it to themselves, and they think they're going to get a competitive advantage," he said.

"I'm thinking, who cares? We can all sink together because we're hiding the information, or we can all swim together and everybody's going to get a little bit rich in the process, not filthy rich."

Contact the writer: llegere@timesshamrock.com.

DEMAND ACCOUNTABILITY!

There are lots of wastewater treatment systems that run effectively in Canada. How come this company can't provide an effective solution to this kind of problem? Moreover, the difficulty in Marcellus Shale drilling can still be solved if they can start as soon as possible.

ReplyDelete