ProPublica

December 31, 2009

It takes brute force to wrest natural gas from the earth. Millions of gallons of chemical-laden water mixed with sand -- under enough pressure to peel paint from a car -- are pumped into the ground, pulverizing a layer of rock that holds billions of small bubbles of gas.

The chemicals transform the fluid into a frictionless mass that works its way deep into the earth, prying open tiny cracks that can extend thousands of feet. The particles of sand or silicon wedge inside those cracks, holding the earth open just enough to allow the gas to slip by.

Gas drilling is often portrayed as the ultimate win-win in an era of hard choices: a new, 100-year supply of cleaner-burning fuel, a risk-free solution to the nation’s dependence on foreign energy. In the next 10 years, the United States will use the fracturing technology to drill hundreds of thousands of new wells astride cities, rivers and watersheds. Cash-strapped state governments are pining for the revenue and the much-needed jobs that drilling is expected to bring to poor, rural areas.

Drilling companies assert that the destructive forces unleashed by the fracturing process, including the sometimes toxic chemicals that keep the liquid flowing, remain safely sealed as much as a mile or more beneath the earth, far below drinking water sources and the rest of the natural environment.

More than a year of investigation by ProPublica, however, shows that the issues are far less settled than the industry contends, and that hidden environmental costs could cut deeply into the anticipated benefits.

...

For example, it remains unclear how far the tiny fissures that radiate through the bedrock from hydraulic fracturing might reach, or whether they can connect underground passageways or open cracks into groundwater aquifers that could allow the chemical solution to escape into drinking water. It is not certain that the chemicals – some, such as benzene, that are known to cause cancer – are adequately contained by either the well structure beneath the earth or by the people, pipelines and trucks that handle it on the surface. And it is unclear how the voluminous waste the process creates can be disposed of safely.

...ProPublica has uncovered more than a thousand reports of water contamination from drilling across the country, some from surface spills and some from seepage underground. In many instances the water is contaminated with compounds found in the fluids used in hydraulic fracturing. ProPublica also found dozens of homes in Ohio, Pennsylvania and Colorado in which gas from drilling had migrated through underground cracks into basements or wells.

...

ProPublica has also found that drilling procedures that can prevent water pollution and sharply reduce toxic air emissions – another frequent side effect -- are seldom required by state regulators and are mostly practiced when and where the industry wishes.

Another uncertainty arises from the enormous amounts of water needed for “fracking.” The government estimates that companies will drill at least 32,000 new gas wells annually by 2012. That could mean more than 100 billion gallons of hazardous fluids will be used and disposed of each year if existing techniques, which often involve 4 million gallons of water per well, are used.

...

How will the wastewater be safely disposed of?

Are regulations in place to make sure the gas is extracted as safely as possible?

...A recent regional government study in Colorado concluded that the same methane gas tapped by drilling had migrated into dozens of water wells, possibly through natural faults and fissures exacerbated by hydraulic fracturing.

...

In another case, benzene, a chemical sometimes found in drilling additives, was discovered throughout a 28-mile long aquifer in Wyoming.

...

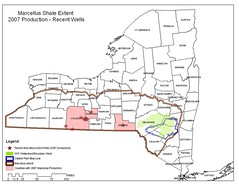

Where Should the Waste Go?

Most drilling wastewater in other parts of the country is stored in underground injection wells that are regulated by EPA under the Safe Drinking Water Act. However the geology in the East makes injection less viable, and less common. In New York and Pennsylvania, millions of gallons of drilling wastewater could eventually be produced each day.

That wastewater will likely be trucked to treatment plants that don’t routinely test for most of the chemicals the wastewater contains and that may not be equipped to remove them. Currently, the plants also can’t remove the high levels of Total Dissolved Solids found in drilling wastewater – a mixture of salts, metals and minerals – that can increase the salinity of fresh water streams and interfere with the biological treatment process at sewage treatment plants, allowing untreated waste to flow into waterways. High TDS levels also can harm industrial and household equipment and affect the color and taste of water.

After the wastewater passes through the treatment plants, it is dumped back into public waterways that supply drinking water to at least 27 million Americans, including residents of Philadelphia and New York City. But without identification and routine testing for the problematic chemicals, it will be impossible to know how much of them are making their way to drinking water sources, or how they are accumulating over time. Evolving medical science says low-dose exposure to some of those chemicals could have much greater health effects than the EPA or doctors have previously thought.

“Managing produced water has always seemed like one of the large challenges, because this area geologically doesn’t have the extensive network of underground injection wells,” said Lee Fuller, vice president of government relations for the Independent Petroleum Association of America. “One challenge that industry has got is looking at developing [treatment] technology, which could be very costly.”

All Equal Under the Law

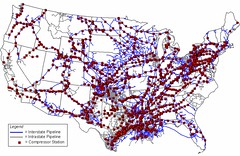

The gas industry, and hydraulic fracturing, is subject to widely different laws in different states. Some of those laws are tough, perhaps burdening the drilling industry unnecessarily. Others are lenient, perhaps leaving much of the country subject to environmental danger.

One thing is certain: There is no national standard for an industrial process that is used prolifically in 32 states and will be used even more in the future.

...

... It remains to be seen whether politicians and environmental regulators will make sure precautions are taken at the beginning of this new energy boom, or if they will leave the nation to clean up the mess after the boom goes bust, as it has had to do so many times in the past.

To continue reading the important information contained in this thorough exposé, PLEASE CLICK HERE.

DEMAND ACCOUNTABILITY!

Be careful dealing with these gas production companies. Our experience with them has been that they will privatize the profits and socialize the cleanup costs of oil and gas production. Landowners and taxpayers end up getting stuck with the bill for cleanup of radioactive waste at well sites. Don't make the same mistakes we made.

ReplyDelete