Posted: Saturday, December 19, 2009 11:55 pm

CASPER — Expect the issue of water conservation to gain more interest in discussions of energy development — be it green, black or somewhere between.

The arid West is likely become more arid with climate change, according to the world’s top scientists, and no longer will residents and municipalities yawn at the prospect of drilling a new well to cool a coal power plant or solar power facility.

And credit Exxon Mobil for bringing a new level of national attention to the practice of hydraulic fracturing, with its $31 billion bid for XTO Energy this past week.

Hydraulic fracturing is the practice of pumping sand and fluids — often diesel fuel — into natural-gas-bearing rock, creating fractures in the rock that allow the natural gas to flow to the production well.

EPA retains the authority to regulate the use of diesel fuel for the purpose of hydraulic fracturing if the agency considers such regulation necessary to protect underground sources of drinking water.

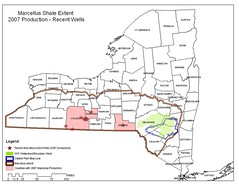

XTO Energy holds 280,000 acres in the Marcellus Shale in Pennsylvania. Residents and environmental groups concerned about maintaining groundwater quality expect that Exxon Mobil, with its deeper pockets, will perforate and “frack” on a scale unseen even in Wyoming’s Jonah and Pinedale Anticline.

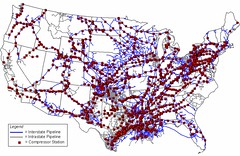

Already, a hearing has been called for by a congressional subcommittee regarding Exxon Mobil’s big leap into the unconventional natural gas play. Environmental concerns were listed as a key issue, as well as what seems to be an appetite to shift more of the nation’s base-load electrical generation to natural gas.

Hydraulic fracturing has increased the nation’s recoverable natural gas resource 35 percent in just two years. However, nearly all of that resource is intermingled with water.

State Rep. Jeb Steward, R-Encampment, told me recently that water conservation deserves to be a prominent part of any discussion about energy development.

And perhaps one of the biggest water-and-energy challenges in Wyoming will be carbon sequestration in the Rock Springs Uplift, where the state engineer expects liquefied CO2 will replace briny groundwater on a one-to-one basis.

Computer modeling has suggested that CO2 injections over a 75-year period in the Rock Springs Uplift could require pumping 1 cubic kilometer to the surface — about the volume of Boysen Reservoir.

“We’re going to be having produced water issues, I think, of a magnitude that will be significant,” Steward said.

LINK.

No comments:

Post a Comment