(co-published with Politico)

that for each modern gas well drilled in the Marcellus and places like

it, more than three million gallons of chemically tainted wastewater

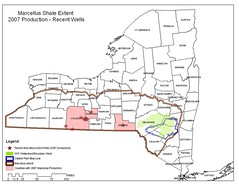

could be left in the ground forever. (Photo courtesy of the New York

State Environmental Impact Statement)

For more than a decade the energy industry has steadfastly argued before courts, Congress and the public that the federal law protecting drinking water should not be applied to hydraulic fracturing, the industrial process that is essential to extracting the nation's vast natural gas reserves. In 2005 Congress, persuaded, passed a law prohibiting such regulation.

Now an important part of that argument -- that most of the millions of gallons of toxic chemicals that drillers inject underground are removed for safe disposal, and are not permanently discarded inside the earth -- does not apply to drilling in many of the nation's booming new gas fields.

Three company spokesmen and a regulatory official said in separate interviews with ProPublica that as much as 85 percent of the fluids used during hydraulic fracturing is being left underground after wells are drilled in the Marcellus Shale, the massive gas deposit that stretches from New York to Tennessee.

That means that for each modern gas well drilled in the Marcellus and places like it, more than three million gallons of chemically tainted wastewater could be left in the ground forever. Drilling companies say that chemicals make up less than 1 percent of that fluid. But by volume, those chemicals alone still amount to 34,000 gallons in a typical well.

These disclosures raise new questions about why the Safe Drinking Water Act, the federal law that regulates fluids injected underground so they don't contaminate drinking water aquifers, should not apply to hydraulic fracturing, and whether the thinking behind Congress' 2005 vote to shield drilling from regulation is still valid.

When lawmakers approved that exemption, it was generally accepted that only about 30 percent of the fluids stayed in the ground. At the time, fracturing was also used in far fewer wells than it is today and required far less fluid. Ninety percent of the nation's wells now rely on the process, which is widely credited for making it financially feasible to tap into the Marcellus Shale and other new gas deposits.

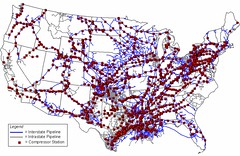

Congress is considering a bill that would repeal the exemption, and has directed the Environmental Protection Agency to undertake a fresh study of how hydraulic fracturing may affect drinking water supplies. But the government faces stiff pressure from the energy industry to maintain the status quo -- in which gas drilling is regulated state by state -- as companies race to exploit the nation's vast shale deposits and meet the growing demand for cleaner fuel. Just this month, Exxon announced it would spend some $31 billion to buy XTO Energy, a company that controls substantial gas reserves in the Marcellus -- but only on the condition that Congress doesn't enact laws on fracturing that make drilling "commercially impracticable."

The realization that most of the chemicals and fluids injected underground remain there could stoke the debate further, especially since it contradicts the industry's long-standing message that only a small proportion of the fluids is left behind at most wells.

But while the message has not changed, the drilling has.

The Marcellus Shale, denoted in brown, primarily cuts across large swaths of New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia. (Map by Jennifer LaFleur/ProPublica)

During hydraulic fracturing, drillers use combinations of some of the 260 chemical additives associated with the process, plus large amounts of water and sand, to break rock and release gas. Benzene and formaldehyde, both known carcinogens, are among the substances that are commonly found.

If another industry proposed injecting chemicals -- or even salt water -- underground for disposal, the EPA would require it to conduct a geological study to make sure the ground can hold those fluids without leaking and to follow construction standards when building the well. In some cases the EPA would also establish a monitoring system to track what happens as the well ages.

But because hydraulic fracturing is exempt from the Safe Drinking Water Act, it doesn't necessarily have to conform to these federal standards. Instead, oversight of the drilling chemicals and the injection process has been left solely to the states, some of which regulate parts of the process while others do not.

As the industry was lobbying Congress for that exemption -- and ever since -- the notion that most fluids would not be left underground continued to emerge as a recurring theme put forth by everyone from attorneys for Halliburton, which developed the fracturing process and is one of the leading drilling service companies, to government researchers and regulators.

"Hydraulic fracturing is fundamentally different," wrote Mike Paque, director of the Ground Water Protection Council, an association of state oil and gas regulators, to Senate staff in a 2002 letter advocating for the exemption, "because it is part of the well completion process, does not 'dispose of fluids' and is of short duration, with most of the fluids being immediately recovered."

In May, ProPublica heard a similar explanation from the industry-funded American Petroleum Institute.

"Hydraulic fracturing operations are something that are done from 24 hours to a couple of days versus a program where you are injecting products into the ground and they are intended to be sequestered for time into the future," said Stephanie Meadows, a senior API policy analyst who has been closely involved in fracturing legislation issues. "I don't see the benefit of trying to take that sort of sequestration type activity and applying it to something that is temporary in time."

Asked how much fracturing fluid can remain underground, and whether it could be as high as 30 percent, the figure that was still being included in government reports earlier this year, Meadows said: "I guess I didn't know that the statistics are that high."

Neither the American Petroleum Institute nor the Ground Water Protection Council responded to requests for further comment.

EPA officials maintained in 2005, and say now, that the volume of fluids left underground had little to do with its opinion that hydraulic fracturing for gas wells is not the same as underground injection. They say that distinction is because the primary function of the two types of wells is different: Gas wells are for production processes, while most EPA-regulated underground injection wells are intended for storage.

But Stephen Heare, director of the EPA's Drinking Water Protection Division in Washington, said that both the circumstances and the drilling technology have evolved. When asked to explain how hydraulic fracturing today is different from other forms of underground injection, he said the bottom line was simple.

"If you are emplacing fluid, it does not matter whether you are recovering 30 percent or 65 percent of it, if you are emplacing fluids, that is underground injection," Heare said. "The simple explanation for why hydraulic fracturing is different from other injection activities," he added, is that hydraulic fracturing "is exempt from regulation under the Safe Drinking Water Act."

Continue reading HERE.

DEMAND ACCOUNTABILITY!

No comments:

Post a Comment