Victoria Switzer gives her pets bottled water because gas drilling

Victoria Switzer gives her pets bottled water because gas drillingby Cabot Oil and Gas has contaminated their water well in Dimock, Pa.

photo: Fred R. Conrad/The New York Times

DIMOCK, Pa. — Victoria Switzer dreamed of a peaceful retirement in these Appalachian hills. Instead, she is coping with a big hassle after a nearby natural gas well contaminated her family’s drinking water with high levels of methane.

Through no design of hers, Ms. Switzer has joined a rising chorus of voices skeptical of the nation’s latest energy push.

“It’s been ‘drill, baby, drill’ out here,” Ms. Switzer said bitterly. “There is no stopping this train.”

...

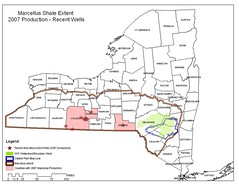

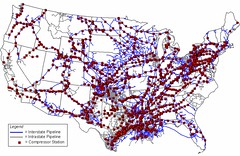

The drilling boom is raising concern in many parts of the country, and the reaction is creating political obstacles for the gas industry. Hazards like methane contamination of drinking water wells, long known in regions where gas production was common, are spreading to populous areas that have little history of coping with such risks, but happen to sit atop shale beds.

And a more worrisome possibility has come to light. A string of incidents in places like Wyoming and Pennsylvania in recent years has pointed to a possible link between hydraulic fracturing and pollution of ground water supplies. In the worst case, such pollution could damage crucial supplies of water used for drinking and agriculture.

...

The debate is becoming more urgent as gas companies move closer to more populated areas, especially in the Northeast, where millions of people are likely to find themselves living near drilling operations in coming years.

“To be able to scale up our drilling, clearly we have to be in sync with people’s concerns about water,” said Aubrey K. McClendon, chairman and chief executive of the Chesapeake Energy Corporation, a leading gas company. “It’s our biggest challenge.”

“It’s a very reliable, safe, American source of energy,” said John Richels, president of the Devon Energy Corporation.

Environmental activists, however, say there is at least scattered evidence that fracturing operations can pose risks to ground water sources, particularly when mistakes are made in drilling operations. They have also questioned how some companies deal with the wastewater produced by their operations, warning that liquids laced with chemicals and salt from drilling can overload public sewage treatment plants or pollute surface waters.

Deborah Goldberg, a lawyer for the nonprofit environmental group Earthjustice who is fighting to toughen Pennsylvania’s discharge rules, said the state “is facing enormous pressure from gas drillers, who are generating contaminated water faster than the state’s treatment plants can handle it.”

According to the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, which is going through a public review of its new rules on hydraulic fracturing, gas companies use at least 260 types of chemicals, many of them toxic, like benzene. These chemicals tend to remain in the ground once the fracturing has been completed, raising fears about long-term contamination.

The most immediate hazard from the national drilling bonanza, it is clear, involves contamination of residential drinking water wells by natural gas. In Bainbridge, Ohio, an improperly drilled well contaminated ground water in 2007, including the water source for the township’s police station, according to a complaint filed this year. After building to high pressures, gas migrated through underground faults, and blew up one house.

Here in Dimock, about 35 miles northwest of Scranton, Pa., 13 water wells, including that of Ms. Switzer, were contaminated by natural gas. One of the wells blew up.

Under prodding, environmental regulators are stepping up the search for ground water contamination. In Pavilion, Wyo., for instance, the Environmental Protection Agency has begun an investigation into contamination of several drinking water wells.

Luke Chavez, an E.P.A. investigator, said that traces of methane and 2-butoxyethanol phosphate, a foaming agent, had been found in several wells near an area where the EnCana Corporation, a Canadian gas company, had used hydraulic fracturing in recent years.

He said the compounds could have come from cleaning products or oil and gas production, but “it tells us something is happening here that shouldn’t be here.”

...

In a 2004 study, the E.P.A. decided that hydraulic fracturing was essentially harmless. Critics said the analysis was politically motivated, but it was cited the following year when the Republican-led Congress removed hydraulic fracturing from any regulation under the Safe Drinking Water Act.

The current Democratic Congress recently enacted a law requiring the E.P.A. to review the study. Lawmakers from Colorado and New York have also introduced legislation to end the water act exemption and require gas companies to disclose all chemicals used in fracturing operations.

...

Partly in response to opposition it has encountered in New York, Chesapeake recently indicated that it would not drill in the New York City watershed, a region that supplies drinking water to nearly 10 million people. Schlumberger, a service company that performs fracturing operations on behalf of gas companies, said it was working on “green” fracturing fluids, including safer substitutes for hazardous chemicals.

In the Barnett shale gas field in Texas, Devon Energy and Chesapeake are trying various treatment techniques for disposing of contaminated drilling water. Gas executives hope that wider use of such techniques will damp public opposition in some regions. Several companies are starting a joint water treatment effort in Pennsylvania in the next few weeks.

Still, around Dimock, the gas boom is viewed with mixed feelings. ...

In September, the Cabot Oil and Gas Corporation, a Houston energy company, was required to suspend its fracturing operations for three weeks after causing three spills in the course of nine days. Cabot, which was fined $56,650 by the state, said the spills consisted mainly of water, with only 0.5 percent chemicals. This month, Cabot was fined an additional $120,000 by Pennsylvania for the contamination of homeowners’ wells. It must now submit strict drilling plans to the state.

A company spokesman, Kenneth S. Komoroski, said it was too early to blame hydraulic fracturing — the technology at the heart of the boom — for pollution of water wells. He said Cabot was still investigating the causes of last January’s contamination incidents.

“None of the issues in Dimock have anything to do with hydraulic fracturing,” he said.

The fines were little consolation to Ms. Switzer, the woman who can no longer draw drinking water from her well.

...

Her family now uses bottled water supplied by Cabot every week. She fears that if she tried to sell her home, which sits in the middle of a drilling zone, no one would buy it.

“Can you imagine the ad? ‘Beautiful new home. Bring your own water,’ ” Ms. Switzer said. “We’re like a dead zone here.”

For the complete article, CLICK HERE.

DEMAND ACCOUNTABILITY!

No comments:

Post a Comment