Showing posts with label Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act. Show all posts

Wednesday, March 25, 2009

Oversight of chemicals used in gas drilling unclear... AND OUTRAGEOUS!

Scranton (PA) Times-Tribune: Oversight of chemicals used in gas drilling unclear

BY LAURA LEGERE

STAFF WRITER

Published: Monday, March 23, 2009 4:22 PM EDT

BRIDGEWATER TWP. — Cabot Oil and Gas began storing dozens of 55-gallon drums marked “methanol” on a Susquehanna County lot last winter about 100 feet and a crumbling fieldstone wall away from Matthew Nebzydoski’s backyard and his 4-year-old daughter’s swing set.

A resident recently contacted the county emergency management agency with photos of the drums, each of which is clearly labeled with a skull and crossbones, as well as several pictures of a barrel tipped over with a puncture through its side. The emergency agency forwarded the complaint to the Department of Environmental Protection, which generally regulates natural gas drilling in the state.

On March 12, DEP inspected the site and found no violations for spills, leaks or waste problems — the aspects of the site the department can regulate because the agency does not have oversight of chemical products stored in small containers, a spokesman said.

Despite the clean inspection, the barrels of methanol so close to a residential neighborhood raised questions about the toxic chemicals natural gas drilling is introducing in rural areas neither prepared nor zoned to deal with them.

Methanol, which gas operators use as an antifreeze in pipes, is considered hazardous by national and international fire, health and safety agencies. It is fatal to humans who swallow as little as 4 ounces; two teaspoons can cause blindness. But state and federal storage regulations for hazardous chemicals don’t bar companies from storing large quantities in open air without fences, even when small children live next door.

The methanol in the pipe yard next to Mr. Nebzydoski’s property also revealed uncertainty among state agencies about who regulates the storage of chemicals involved in gas drilling. Both county and state emergency management officials said they believe DEP regulates chemical storage at gas drilling sites, but an inquiry to a DEP spokesman about proper storage was forwarded to the Department of Labor and Industry.

A Department of Labor and Industry spokesman said, “DEP has specific requirements for storage of chemicals related to gas drilling, not PENNSAFE,” the Labor and Industry division that oversees the reporting of hazardous chemicals.

When asked whose jurisdiction the inspection of methanol storage in Bridgewater Twp. falls under, Mark Carmon, the regional DEP spokesman, said unless it violates a local ordinance, “I don’t know if it all falls under anybody. It’s an equipment storage yard.”

'You can see the poison labels from here'

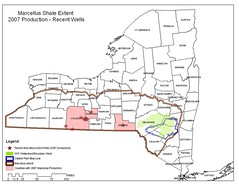

Concerns about the chemicals used in the gas extraction process — particularly those chemicals mixed with water and sand and injected underground to fracture the gas-bearing Marcellus Shale — are often met with an insistence the chemicals make up a minute part of the millions of gallons of fracturing fluid used to stimulate each gas well.

But before the chemicals are diluted they are stored in concentrated amounts in places like the Cabot Oil and Gas Pipe Yard off Route 29.

On Tuesday evening, Mr. Nebzydoski stood in his yard while his daughter, Maggie, played in a dirt pile and told herself a story about an imaginary garden.

Four years ago, when the middle school principal moved his family to the neighborhood — one of the rare residential developments in the rural townships just south of Montrose — the storage yard next door was a green field.

“You turn and look this way,” he said, glancing at the circle of tidy neighboring homes “and you see the perfect American dream-type neighborhood. You turn the other way and you see that.” He nodded at the dozens of black methanol barrels stacked against the side of a trailer, plastic totes of purple and yellow chemicals used in the process of drilling for gas and, to the left, storage tanks, construction vehicles and a pile of long teal pipes.

“You can see the poison labels from here,” he said.

Nothing but the fallen wall and a narrow strip of brush separates his yard from the industrial site — a concern in a neighborhood with about 20 children, he said. At the entrance to the pipe yard from Route 29 there is only a small sign, for the self-storage facility that shares the lot, that declares “absolutely no trespassing.”

Mr. Nebzydoski believes local ordinances and zoning districts might have prohibited an industrial storage yard from locating next door to his neighborhood, but Bridgewater Twp., like most municipalities in Susquehanna County, is not zoned.

The township is pursuing zoning, but some vocal residents have rallied against it, worrying it will stifle economic development, according to township Supervisor Charles Mead.

Although the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and National Fire Protection Association set protocols for how flammable and combustible liquids must be stored, they do not prohibit storage outside or without fences.

A Cabot spokesman said although there are dozens of drums marked methanol in the yard, a check Friday afternoon revealed only 11 were full. The other 59 were empty and waiting to be sent back to a supplier to be refilled. Cabot never stores as many as 24 full barrels in the yard at once, he said.

He also explained the storage yard is temporary and the company has for some time been working to establish a fenced, permanent storage yard and building farther south on Route 29.

“The plan has been all along not to have those drums there long term,” the spokesman, Ken Komoroski, said.

Rules only go so far

Federal and state regulations that address the storage of hazardous chemicals are meant to help communities prepare for toxic dangers in their towns, but natural gas development in the region has also revealed the limits of those rules.

Federal law dictates facilities that store hazardous chemicals above a certain threshold, usually 10,000 pounds, must report it to state and local emergency response agencies, including the local fire department.

Called the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act, the federal regulations are meant to inform emergency responders and residents about where hazardous chemicals are being produced or used in their communities.

But oil and gas operators have adopted generic reporting terms that allow them to disclose categories of chemicals, like “solvents” or “surfactants,” rather than specific chemicals stored at each site. Some states, including Texas, do not accept generic reporting.

In Pennsylvania, if oil and gas companies use generic descriptions, they still have to identify what chemicals are used and in what percentage, a spokesman for the state Department of Labor and Industry said. Furthermore, companies in the state must submit site plans along with chemical inventory reports pinpointing exactly where at a facility chemicals are stored.

***But a review of Cabot chemical inventory reports submitted to the Susquehanna County Emergency Management Agency in the last three years revealed the forms are often vague and inconsistent.

None of the four chemical inventory reports the company has filed include site plans. On one form, Cabot indicates diesel fuel poses a fire hazard; on another it indicates it does not. Each of the forms is stamped with instructions to consult the generic hazardous chemical inventory for the oil and gas industry, which lists the “categories of hazardous chemicals rather than the trade names and specific chemical names.”

In total, the Cabot reports disclose “cement,” “diesel fuel,” “drilling mud,” “fracture fluids,” “produced hydrocarbons,” “proppants” and “associated additives” as the hazardous chemicals found in reportable quantities across 21 well sites.

The reports do not specifically list the presence of methanol because Cabot has never reached the reportable threshold for the chemical, Mr. Komoroski said.

“We receive barrels in and we send the barrels back to be refilled. We never exceed the threshold. We have never even approached that.”

He could not answer specific questions about how Cabot uses generic reporting because, he said, the company hires a “professional experienced consultant” to create its chemical inventory reports.

“We do believe that the company is fully complaint with its (chemical inventory) reporting obligations now,” he said.

(New contradictions?)

He also said Cabot conducts regular training sessions with the local fire company where information about hazardous chemicals is provided to first responders.

According to the local fire chief, Cabot has not submitted the reports to the Springville Volunteer Fire Company, the local fire department. On its reports for the county emergency management agency, Cabot listed the local fire company as “Dimock,” which does not exist.

Firefighters unprepared

In the last year, Chief Dan Smales, of Springville Volunteer Fire Company, has seen his small, country fire company called to industrial-type incidents as gas development has increased in the region.

He said the volunteer firefighters have learned on the job at each incident — a diesel spill, an accidental injury, gas flares — without specific training.

He also said the lack of chemical inventory reports sent to his department — and the lack of clarity on the ones submitted to the county emergency management agency — are cause for concern. For example, he said, the term “fracture fluids” on Cabot’s report does not clarify the risks for him.

“We have no idea what that stuff is,” he said. “We don’t know. They haven’t told us.”

That lack of information has defined much of his fire company’s experience with gas drilling so far. Most often, when the firefighters respond to a call, Cabot well tenders or contracted hazardous materials teams have already taken care of the problem, he said.

This week, Cabot is holding a dinner and training session for a few members of each area fire company, but although Chief Smales said Cabot has been “great to work with,” he does not know what he will learn at the training, or even what he would like to learn.

“I think the biggest thing is, what do we do if? What if a well does catch fire, is there a valve to shut off. How do you stop it? I don’t know.”

In the meantime, the firefighters want to protect the community and the community wants more information, putting first responders in a difficult position.

“I think there are a lot of questions and people want answers and I don’t have them,” he said.

Chemicals listed on DEP Web site

The state Department of Environmental Protection published a list of chemicals found in natural gas operators’ hydraulic fracturing solutions on its Web site for the first time Friday.

The list includes the vendor names of products used by the operators in the state and the hazardous chemicals, by weight, in each of those products.

The list can be viewed at www.dep.state.pa.us/dep/deputate/minres/oilgas/FractListing.pdf

Contact the writer: llegere@timesshamrock.com

Copyright © 2009 - The Times-Tribune

(Editorializing by SPLASH)

BY LAURA LEGERE

STAFF WRITER

Published: Monday, March 23, 2009 4:22 PM EDT

BRIDGEWATER TWP. — Cabot Oil and Gas began storing dozens of 55-gallon drums marked “methanol” on a Susquehanna County lot last winter about 100 feet and a crumbling fieldstone wall away from Matthew Nebzydoski’s backyard and his 4-year-old daughter’s swing set.

A resident recently contacted the county emergency management agency with photos of the drums, each of which is clearly labeled with a skull and crossbones, as well as several pictures of a barrel tipped over with a puncture through its side. The emergency agency forwarded the complaint to the Department of Environmental Protection, which generally regulates natural gas drilling in the state.

On March 12, DEP inspected the site and found no violations for spills, leaks or waste problems — the aspects of the site the department can regulate because the agency does not have oversight of chemical products stored in small containers, a spokesman said.

Despite the clean inspection, the barrels of methanol so close to a residential neighborhood raised questions about the toxic chemicals natural gas drilling is introducing in rural areas neither prepared nor zoned to deal with them.

Methanol, which gas operators use as an antifreeze in pipes, is considered hazardous by national and international fire, health and safety agencies. It is fatal to humans who swallow as little as 4 ounces; two teaspoons can cause blindness. But state and federal storage regulations for hazardous chemicals don’t bar companies from storing large quantities in open air without fences, even when small children live next door.

The methanol in the pipe yard next to Mr. Nebzydoski’s property also revealed uncertainty among state agencies about who regulates the storage of chemicals involved in gas drilling. Both county and state emergency management officials said they believe DEP regulates chemical storage at gas drilling sites, but an inquiry to a DEP spokesman about proper storage was forwarded to the Department of Labor and Industry.

A Department of Labor and Industry spokesman said, “DEP has specific requirements for storage of chemicals related to gas drilling, not PENNSAFE,” the Labor and Industry division that oversees the reporting of hazardous chemicals.

When asked whose jurisdiction the inspection of methanol storage in Bridgewater Twp. falls under, Mark Carmon, the regional DEP spokesman, said unless it violates a local ordinance, “I don’t know if it all falls under anybody. It’s an equipment storage yard.”

'You can see the poison labels from here'

Concerns about the chemicals used in the gas extraction process — particularly those chemicals mixed with water and sand and injected underground to fracture the gas-bearing Marcellus Shale — are often met with an insistence the chemicals make up a minute part of the millions of gallons of fracturing fluid used to stimulate each gas well.

But before the chemicals are diluted they are stored in concentrated amounts in places like the Cabot Oil and Gas Pipe Yard off Route 29.

On Tuesday evening, Mr. Nebzydoski stood in his yard while his daughter, Maggie, played in a dirt pile and told herself a story about an imaginary garden.

Four years ago, when the middle school principal moved his family to the neighborhood — one of the rare residential developments in the rural townships just south of Montrose — the storage yard next door was a green field.

“You turn and look this way,” he said, glancing at the circle of tidy neighboring homes “and you see the perfect American dream-type neighborhood. You turn the other way and you see that.” He nodded at the dozens of black methanol barrels stacked against the side of a trailer, plastic totes of purple and yellow chemicals used in the process of drilling for gas and, to the left, storage tanks, construction vehicles and a pile of long teal pipes.

“You can see the poison labels from here,” he said.

Nothing but the fallen wall and a narrow strip of brush separates his yard from the industrial site — a concern in a neighborhood with about 20 children, he said. At the entrance to the pipe yard from Route 29 there is only a small sign, for the self-storage facility that shares the lot, that declares “absolutely no trespassing.”

Mr. Nebzydoski believes local ordinances and zoning districts might have prohibited an industrial storage yard from locating next door to his neighborhood, but Bridgewater Twp., like most municipalities in Susquehanna County, is not zoned.

The township is pursuing zoning, but some vocal residents have rallied against it, worrying it will stifle economic development, according to township Supervisor Charles Mead.

Although the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and National Fire Protection Association set protocols for how flammable and combustible liquids must be stored, they do not prohibit storage outside or without fences.

A Cabot spokesman said although there are dozens of drums marked methanol in the yard, a check Friday afternoon revealed only 11 were full. The other 59 were empty and waiting to be sent back to a supplier to be refilled. Cabot never stores as many as 24 full barrels in the yard at once, he said.

He also explained the storage yard is temporary and the company has for some time been working to establish a fenced, permanent storage yard and building farther south on Route 29.

“The plan has been all along not to have those drums there long term,” the spokesman, Ken Komoroski, said.

Rules only go so far

Federal and state regulations that address the storage of hazardous chemicals are meant to help communities prepare for toxic dangers in their towns, but natural gas development in the region has also revealed the limits of those rules.

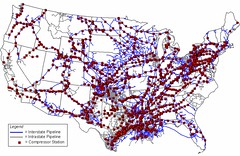

Federal law dictates facilities that store hazardous chemicals above a certain threshold, usually 10,000 pounds, must report it to state and local emergency response agencies, including the local fire department.

Called the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act, the federal regulations are meant to inform emergency responders and residents about where hazardous chemicals are being produced or used in their communities.

But oil and gas operators have adopted generic reporting terms that allow them to disclose categories of chemicals, like “solvents” or “surfactants,” rather than specific chemicals stored at each site. Some states, including Texas, do not accept generic reporting.

In Pennsylvania, if oil and gas companies use generic descriptions, they still have to identify what chemicals are used and in what percentage, a spokesman for the state Department of Labor and Industry said. Furthermore, companies in the state must submit site plans along with chemical inventory reports pinpointing exactly where at a facility chemicals are stored.

***But a review of Cabot chemical inventory reports submitted to the Susquehanna County Emergency Management Agency in the last three years revealed the forms are often vague and inconsistent.

None of the four chemical inventory reports the company has filed include site plans. On one form, Cabot indicates diesel fuel poses a fire hazard; on another it indicates it does not. Each of the forms is stamped with instructions to consult the generic hazardous chemical inventory for the oil and gas industry, which lists the “categories of hazardous chemicals rather than the trade names and specific chemical names.”

In total, the Cabot reports disclose “cement,” “diesel fuel,” “drilling mud,” “fracture fluids,” “produced hydrocarbons,” “proppants” and “associated additives” as the hazardous chemicals found in reportable quantities across 21 well sites.

The reports do not specifically list the presence of methanol because Cabot has never reached the reportable threshold for the chemical, Mr. Komoroski said.

“We receive barrels in and we send the barrels back to be refilled. We never exceed the threshold. We have never even approached that.”

He could not answer specific questions about how Cabot uses generic reporting because, he said, the company hires a “professional experienced consultant” to create its chemical inventory reports.

“We do believe that the company is fully complaint with its (chemical inventory) reporting obligations now,” he said.

(New contradictions?)

He also said Cabot conducts regular training sessions with the local fire company where information about hazardous chemicals is provided to first responders.

According to the local fire chief, Cabot has not submitted the reports to the Springville Volunteer Fire Company, the local fire department. On its reports for the county emergency management agency, Cabot listed the local fire company as “Dimock,” which does not exist.

Firefighters unprepared

In the last year, Chief Dan Smales, of Springville Volunteer Fire Company, has seen his small, country fire company called to industrial-type incidents as gas development has increased in the region.

He said the volunteer firefighters have learned on the job at each incident — a diesel spill, an accidental injury, gas flares — without specific training.

He also said the lack of chemical inventory reports sent to his department — and the lack of clarity on the ones submitted to the county emergency management agency — are cause for concern. For example, he said, the term “fracture fluids” on Cabot’s report does not clarify the risks for him.

“We have no idea what that stuff is,” he said. “We don’t know. They haven’t told us.”

That lack of information has defined much of his fire company’s experience with gas drilling so far. Most often, when the firefighters respond to a call, Cabot well tenders or contracted hazardous materials teams have already taken care of the problem, he said.

This week, Cabot is holding a dinner and training session for a few members of each area fire company, but although Chief Smales said Cabot has been “great to work with,” he does not know what he will learn at the training, or even what he would like to learn.

“I think the biggest thing is, what do we do if? What if a well does catch fire, is there a valve to shut off. How do you stop it? I don’t know.”

In the meantime, the firefighters want to protect the community and the community wants more information, putting first responders in a difficult position.

“I think there are a lot of questions and people want answers and I don’t have them,” he said.

Chemicals listed on DEP Web site

The state Department of Environmental Protection published a list of chemicals found in natural gas operators’ hydraulic fracturing solutions on its Web site for the first time Friday.

The list includes the vendor names of products used by the operators in the state and the hazardous chemicals, by weight, in each of those products.

The list can be viewed at www.dep.state.pa.us/dep/deputate/minres/oilgas/FractListing.pdf

Contact the writer: llegere@timesshamrock.com

Copyright © 2009 - The Times-Tribune

(Editorializing by SPLASH)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

RURAL IMPACT VIDEOS, 6 parts

Natural gas development in Colorado, the impacts on communities, environment and public health. A primer for public servants and residents of counties that care for their lifestyles.

Drilling for Gas in Bradford County, PA ... Listen!

Cattle Drinking Drilling Waste!

EPA... FDA... Hello?

How many different ways are we going to have to eat this?

... Thank you TXSharon for all you do! ...

Stay tuned in at http://txsharon.blogspot.com

Landfarms

A film by Txsharon. Thank you Sharon for all you do.

Click HERE to read the complete article on Bluedaze: Landfarms: Spreading Toxic Drilling Waste on Farmland